Introduction

Canada is facing an investment and productivity crisis. Its onerous and lengthy regulatory approval processes are compounding the problem. There is a common misconception that shortening regulatory approval process timelines must come at the expense of environmental oversights and affected Indigenous groups. Canadian regulatory approval processes can and should be implemented in a way that allows projects to proceed in a timely manner, without sacrificing necessary environmental requirements and Indigenous interests.

The impact of regulatory delays

Canada’s regulatory approval processes have been negatively impacting investment because they create uncertainty for investors and negatively affect the financial viability of proposed major projects. Investors will pursue a project if the net present value (NPV) exceeds the cost, but the longer the project timeline stretches, the more the NPV is eroded by inflation and the opportunity costs of foregoing other investments.[1] Consequently, the longer a project timeline stretches, the higher the required return on investment to justify the delay. In a competitive global economy, regulatory delay is a significant barrier to investment.

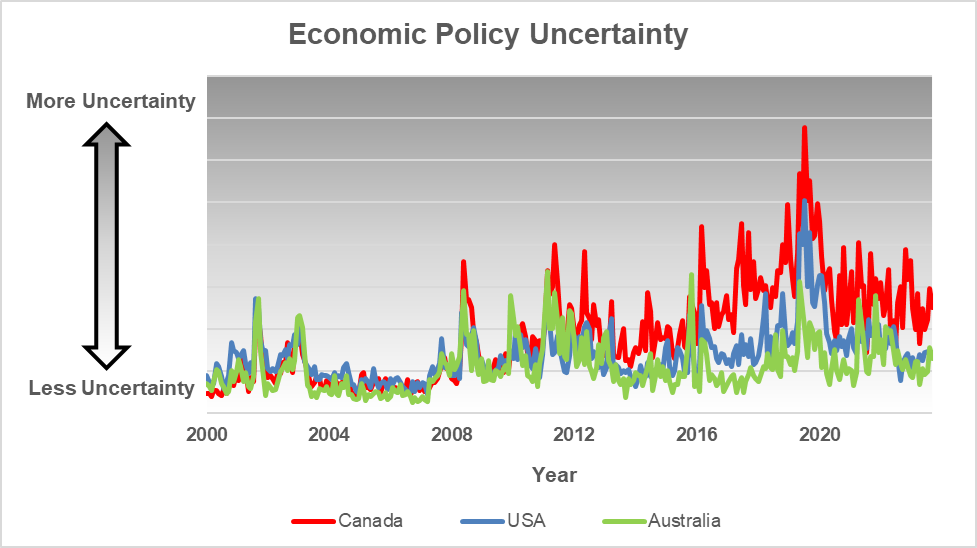

The harm caused by Canada’s regulatory approval processes is not a matter of conjecture, it is supported by data. Figure 1 demonstrates that investors view investing in Canada as higher risk than the United States and Australia, which are Canada’s major competitors for mining and oil and gas investments. This perceived uncertainty is being reflected by fewer dollars being invested. For example, Canada’s estimated global share of mining investment has fallen precipitously. In 2015, Canada accounted for 12% of global mining investment but this figure nearly halved to 7% in 2023.[2]

Economic theorists have understood the positive correlation between investment and productivity for a long time.[3] When investment stalls, productivity suffers. Relative to the United States, Canada is second to last amongst G7 countries when it comes to productivity decline in recent decades.[4]

Further, Canada’s relatively stagnant mining industry appears to conflict with its commitments to decarbonize the economy. Canada is rich in many critical minerals necessary to build a robust low-carbon economy, including copper, manganese, platinum, uranium, lithium, cobalt, indium, tellurium and rare earth elements.[5] Fatih Birol, the executive director of the International Energy Agency (IEA), has suggested he prefers that Canada be a world leader in critical mineral production because “there is rule of law, there is transparency, and there is… accountability of government.”[6] The problem with the IEA is that it has also suggested that there should be no investment in new oil and gas production in order to achieve net-zero.[7] Canada’s federal regulatory process has been used to curtail investment in the development of Canada’s natural resources. This comes at a significant cost to Canada’s economy and productivity.

Canada needs to implement its regulatory approval processes to ensure it can compete with other countries to attract investment and increase its productivity.

Streamlining regulatory approvals

Canada’s current regulatory approval processes for building large projects is a mix of overlapping federal and provincial oversight. Regulatory overlap creates uncertainty. Eliminating regulatory overlap is one way to improve efficiency.

Over the past decade, the federal government has involved itself in the approvals process for major projects like mines. This needs to change. The federal government should accept that provinces have strong environmental assessment and protection regimes and its intervention is not needed to ensure high environmental standards are met.

The Impact Assessment Act (IAA) is the federal government’s primary tool to assess the impacts of major projects. Enacted in 2019, the IAA was supposed to offer streamlined regulatory timelines while maintaining stringent environmental and social standards. However, it was challenged by the Province of Alberta as being ultra vires[9] federal powers.[10] Alberta’s challenge was motivated by the federal government’s use of the IAA to try to force the adoption of caps on climate change emissions. In Reference re Impact Assessment Act, the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) ruled against the federal government and held that the majority of the IAA was unconstitutional.[11] The Supreme Court’s decision brought into question the federal government’s jurisdiction to impose emissions caps on industry in a province.[12]

As a result of the SCC’s ruling, some changes to the IAA were enacted in June 2024. The IAA Reference decision does not bar the federal government from designing environmental legislation, but emphasizes that any contemplated federal environmental legislation must respect the division of powers under the Constitution.[13] However, constitutional litigation is unlikely to solve the problem because the problem is not a legal one – it is a political one. To borrow a western idiom, legislation can continue to be amended and lawyers can argue about constitutional jurisdiction until the cows come home, but what is truly needed is an attitude adjustment that sees the federal government respect that provinces are competent regulators and capable of ensuring environmental protection associated with development of their resources within their borders.

The regulatory approval process for projects related to non-renewable natural resources should be led by the provinces and their regulatory bodies. Regulatory bodies are specialized in particular areas of the law and have the expertise and institutional knowledge necessary to adjudicate regulatory approval processes. Provincial governments and their regulatory bodies can implement requirements that are as stringent as those of the federal government and its regulatory bodies. The issue damaging Canada’s ability to attract capital to develop its resources is not overly stringent or restrictive environmental or social requirements, it is the uncertainty created by duplication in regulation and the perception that at the federal level, Canada is not interested in developing some of its most significant resources.[14] Legislative changes and constitutional challenges are unlikely to be an answer to the problem because they just bring more delay and continue the uncertainty. What is needed is a change in attitude. The regulatory approval processes can be efficient without jeopardizing Canada’s environmental and social goals. Continuous conflict between the federal and provincial governments is highly unproductive.

Through various iterations of legislative change over past 30 years, the federal government has always had the ability to defer to provincial regulatory processes and accept their results in the interests of providing timely decisions and regulatory certainty. The federal government has recently indicated that it wants to change its approach, to achieve these objectives, but only in relation to what it considers to be “Clean Growth Projects.”[15] In order to be effective in creating the certainty needed to attract investment in Canada’s mining industry, the federal government can not be selective in its efforts to streamline its regulatory process. Regulatory certainty requires that all provinces and projects be subject to the same process.

Nowhere is this regulatory inefficiency more apparent than in process to permit a new mine in Canada, which involves both federal and provincial regulators under the IAA and provincial environmental assessment acts, such as British Columbia’s Environmental Assessment Act.[16] The duplication of regulatory oversight across a broad range of social, ethical, cultural and economic impacts, in addition to environmental, health and safety considerations, has left Canada with a process that can extend to 12 – 15 years. Recent recognition of the importance of securing domestic sources for the critical minerals essential for technologies like electric vehicles, renewable energy systems and advanced electronics has drawn much needed attention from political and industry leadership. Presently, the Mining Association of British Columbia (AME), which represents operators of major BC mines, is advocating for a new permitting strategy aimed at reducing mine permitting timelines to seven years. A key element of AME’s strategy is convening joint project tables to streamline and align federal and provincial permitting and authorization processes for designated projects.[17] Recently, both the provincial New Democratic Party and the Conservative Party have made commitments to expedite British Columbia’s mine permitting process, reflecting a growing consensus of the need for a more efficient and streamlined permitting approval processes.

The importance of Indigenous equity partnerships

Indigenous partners can be important to the success of major projects in Canada. Affected Indigenous groups can significantly delay the regulatory approval process, but partnering with them on project development can significantly expedite the regulatory approval process and advance economic reconciliation. Successful business operations in Canada depend on the ability to adapt to the evolving relationship between federal and provincial governments and Indigenous partners, including First Nations communities.

Economic reconciliation, broadly speaking, is an initiative to include Indigenous people, communities and businesses in economic activities. In Alberta and British Columbia, many Indigenous groups are working together with industry to develop large projects as equity partners. Mining projects are well-suited to achieving economic reconciliation because they are geographically confined, allowing for the identification of a limited number of the most affected Indigenous groups to become partners in development.

The reconciliation process remains a priority for the Canadian government, which has demonstrated a willingness to take significant steps to address the matter. Increasingly, First Nations communities are seeking equity ownership rather than jobs, training opportunities and profit-sharing traditionally offered through impact benefit agreements (IBAs). Equity ownership is increasingly viewed by Indigenous communities as representing a step towards true economic self-determination.

Canadian courts have found that First Nations communities have inherent rights to lands demonstrated to be part of their traditional territories; however, First Nations communities have historically faced challenges in monetizing these rights. Recent government programs, such as loan guarantees, are addressing this gap by enabling First Nations to access capital for equity investments. These measures are instrumental in ensuring they can participate more fully in major projects in their territory as equity stakeholders.

In its 2024 budget, the Canadian federal government announced a pledge to establish and fund a national Indigenous loan guarantee program up to CA$5.0 billion through a newly formed, wholly-owned subsidiary of the Canada Development Investment Corporation, the Canada Indigenous Loan Guarantee Corporation.[18] This initiative aims to provide First Nations communities with the financial tools necessary to participate as equity stakeholders in major projects, with the intent of fostering economic reconciliation and enhancing regulatory certainty.

Similarly, British Columbia’s three-year fiscal plan, published in 2024, highlights the importance of meaningful project involvement and ownership opportunities for First Nations communities. To support this, British Columbia introduced the First Nations Equity Framework (the Framework) in 2024, intended to facilitate participation projects through various mechanisms, including equity loan guarantees.[19]

The Framework establishes a First Nations Equity Financing special account, initially funded with CA$19.0 million to address capacity needs and provincial program costs for various projects. Additionally, the British Columbia government has authorized guarantees for equity loans, capped at CA$1.0 billion to help First Nations communities acquire equity stakes in priority projects. Other provinces with loan guarantee programs in place include Alberta, Saskatchewan and Ontario, through the Alberta Indigenous Opportunities Corporation, the Saskatchewan Indigenous Investment Finance Corporation and the Aboriginal Loan Guarantee Program (Ontario), respectively.

Structuring Indigenous equity partnerships

Equity partnerships, often structured as limited partnerships or joint ventures, provide First Nations communities with greater control, equity and financial benefits compared to traditional IBAs. Limited partnerships are often the preferred model due to potential tax advantages under Section 87 of the Indian Act. For example, income earned by an Indigenous partner through a limited partnership connected to reserve lands may be tax-exempt due to its flow-through income structure, which enhances the financial viability of such arrangements. This structure is particularly effective when part of the business is conducted on-reserve, leveraging the tax exemptions to maximize net benefits. By contrast, lump-sum payments or revenue sharing from IBAs are fully taxable, diminishing their overall value.

While equity partnerships present substantial opportunities, several challenges remain. A notable issue is the ambiguity surrounding the legal status of “bands” under Canadian law, which contributes to uncertainty in partnership arrangements.[20] As part of the reconciliation process, certain First Nations communities now possess the legal authority to exercise ownership over traditional lands, grant land rights and licences, manage natural resources and enact laws on those lands.[21]

When pursuing Indigenous equity partnerships, one of the most difficult issues is to identify the groups to partner with. Project equity can be diluted, along with its effectiveness, if participation is too broad. This is a major challenge to linear infrastructure projects that can affect dozens of groups, but is far less of an issue for mining projects that are able to be far more focused in their partnership arrangements. Mining projects can more realistically use economic reconciliation by adding equity to the benefits they offer to achieve informed consent from the most affected groups.

Ultimately, equity partnerships with Indigenous groups represent a valuable approach to resource development, combining economic reconciliation with long-term financial benefits and enhanced project certainty. By addressing challenges such as regulatory overlaps and providing robust financial support mechanisms, these partnerships can significantly advance Canada’s goals for inclusive growth and sustainable development.

Conclusion

Canada’s investment and productivity crises are being compounded by inefficient regulatory approval processes for major projects. Investors are wary of investing in Canada because there is too much uncertainty regarding project approvals and timelines relative to other comparable jurisdictions. As timelines increase, the economic viability of projects decreases and investment dwindles. There are two primary changes that can make Canada more competitive internationally. First, the federal government needs to accept that provinces and their regulatory bodies can ensure the protection of the environment in the development of their natural resources. Second, project proponents can pursue Indigenous equity partnerships as a tool to both smooth the regulatory approval process and advance economic reconciliation.

For more information on this topic, please contact the authors, David Hunter, Bernard Roth or Mary Su. Thank you to our articling student Ben Kriwokon for his significant contribution to this insight.

This article was first published by Canadian Mining Journal

[1] Grant Bishop and Grant Sprague, “A Crisis of Our Own Making: Prospects for Major Natural Resource Projects in Canada” (February 2019) Commentary No. 534 at 15, online (PDF): C.D. Howe Institute <https://www.cdhowe.org/sites/default/files/2024-01/Commentary_534.pdf>.

[2] Charles DeLand and Brad Gilmour, “Smoothing the Path: How Canada Can Make Faster Major-Project Decisions” (June 2024) Commentary No. 661 at 8, online (PDF): C.D. Howe Institute <https://www.cdhowe.org/sites/default/files/2024-06/Commentary_661%20%28002%29.pdf>.

[3] See e.g. Robert M. Solow, “A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth” (1956) 70:1 The Quarterly Journal of Economics 65; See generally “Research to Insights: Investment, Productivity and Living Standards”, online (PDF): Statistics Canada <https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/11-631-x/11-631-x2022004-eng.pdf?st=5Bx1IiJN>; See generally “Investment and Productivity: Why is M&E investment important to labour productivity?”, online: The Conference Board of Canada <https://www.conferenceboard.ca/hcp/investprod-aspx/>.

[4] Carolyn Rogers, “Time to break the glass: Fixing Canada’s productivity problem”, (Speech delivered to the Halifax Partnership, Halifax, NS, 26 March 2024), online (PDF): Bank of Canada < https://www.bankofcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/remarks-2024-03-26.pdf>.

[5] “The Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy” (2022) at 1, online (PDF): Government of Canada <https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/nrcan-rncan/site/critical-minerals/Critical-minerals-strategyDec09.pdf>.

[6] Marieke Walsh & Emma Graney, “Canada needs to move quickly on production of critical minerals, IEA says,” The Globe and Mail, online: <https://www.theglobeandmail.com/politics/article-security-minerals-production-canada-iea/>.

[7] “Pathway to critical and formidable goal of net-zero emissions by 2050 is narrow but brings huge benefits, according to IEA special report” (May 18, 2021), online: International Energy Agency <https://www.iea.org/news/pathway-to-critical-and-formidable-goal-of-net-zero-emissions-by-2050-is-narrow-but-brings-huge-benefits>.

[8] Scott R. Barker, Nick Bloom & Steven J. Davis, “Economic Policy Uncertainty Index”, online: Policy Uncertainty <https://www.policyuncertainty.com/> (This chart was compiled using data from www.policyuncertainty.com, a website maintained by Northwestern University’s Scott R. Barker, Stanford University’s Nick Bloom, and University of Chicago’s Steven J. Davis. To measure policy-related economic uncertainty, an index is constructed using aggregated data from the volume of media coverage discussing policy-related economic uncertainty).

[9] Henry Campbell Black, Black’s Law Dictionary, 6th ed (St. Paul, MN: West Group, 1990), sub verbo “ultra vires” (“An act performed without any authority to act on [the] subject”).

[10] Constitution Act, 1982, s 35, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11, s 92A.

[11] See Reference re Impact Assessment Act, 2023 SCC 23 [IAA Reference].

[12] Dan Collins, Laura K. Estep & Bernie J. Roth, “Lost focus: Supreme Court finds Impact Assessment Act unconstitutional” (October 18, 2023), online: Dentons <https://www.dentons.com/en/insights/articles/2023/october/18/lost-focus-supreme-court-finds-impact-assessment>.

[13] See IAA Reference, supra note 11 at para 216.

[14] Cecilia Jamasmie, “Teck walks away from Frontier oilsands project” (February 24, 2020), online: Mining.com <https://www.mining.com/teck-walks-away-from-frontier-oilsands-project/> (This concern relates to the experience investors have had trying to develop oil and gas resources like Teck Resource’s experience on its Frontier Project in Alberta’s oilsands).

[15] Privy Council Office, “Cabinet Directive on Regulatory and Permitting Efficiency for Clean Growth Products” (July 5, 2024) at Section 4, online: Government of Canada <https://www.canada.ca/en/privy-council/services/clean-growth-getting-major-projects-done/cabinet-directive.html>.

[16] Environmental Assessment Act, S.B.C. 2002, c. 43.

[17] Mining Association of British Columbia, “Permit to Prosperity”, Mining Association of British Columbia, online: <https://mining.bc.ca/permittingprosperity/>.

[18] Department of Finance Canada, “Canada Indigenous Loan Guarantee Corporation”, BC Budget, online: < https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/news/2024/12/canada-indigenous-loan-guarantee-corporation.html>.

[19] “Budget and Fiscal Plan 2024/25 – 2026/27”, Government of British Columbia, online: <https://www.bcbudget.gov.bc.ca/2024/pdf/2024_Budget_and_Fiscal_Plan.pdf>.

[20] Caolan Lemke, Peter Jones & Crista Croos, “Recognition as Reconciliation: First Nations as Direct Shareholders” (November 21, 2025), BC CLE, Aboriginal Law Conference 2024.

[21] One example is the land code developed by the Tsawout First Nation and approved by Canada, pursuant under the First Nations Land Management Act (“FNMLA”), and later preserved in force by the Framework Agreement on First Nation Land Management Act, which repealed and replaced the FNMLA. Other comparable arrangements that highlight the increasing trend of First Nations communities in Canada exercising self-determination over their lands and resources include the Esquimalt Nation, the Anishinabek Nation, and the Nisga’a Nation.